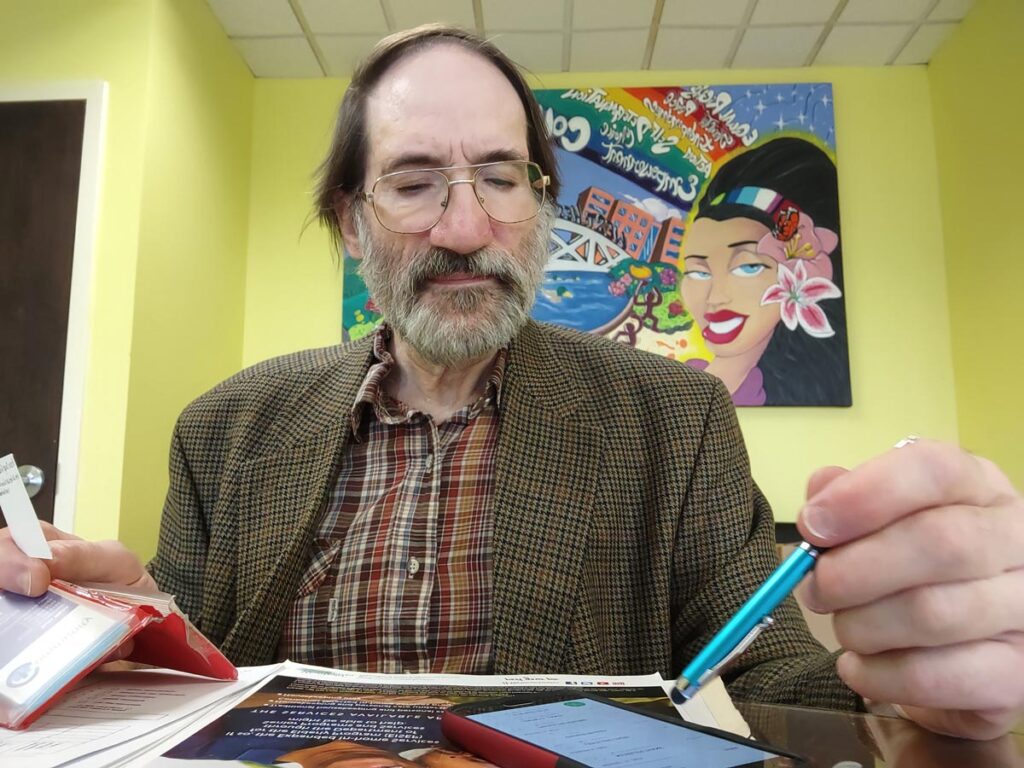

In the disability advocacy field, Supervisor Gerry Hinson’s work stands out for his vital impact and compassionate approach. As a Supervisor in the Nursing Home Transition and Diversion Program (NHTD), Hinson is at the forefront of efforts to empower individuals with disabilities, enabling them to live more independent, fulfilling lives and to have the autonomy and dignity they deserve.

In a nutshell, the NHTD program was created to help seniors and people with physical disabilities receive the services needed to live independently in their community as opposed to a nursing home, congregate care setting, or other institution.

Let’s chat with Gerry who delves into the intricacies of NHTD, including the trials and triumphs of navigating the challenges of disability, transitioning from nursing homes, and his steadfast commitment to fostering a community where every person can thrive.

Please tell us about your overall professional experience within the social services sector and your involvement with WDOM. When were you appointed as the NHTD Program Supervisor at WDOM?

Most of my experience in social services has been serving persons with disabilities within a wide range of settings and characteristics of the persons served. My first 30 years were in the developmental disabilities sphere, starting as an institutional direct care aide while I was still in my 3rd year of college (at NYU) and proceeding to skill teaching, leading activity groups, treatment planning and coordinating, classroom teaching, staff training, and social work assistance. Eventually, I became a case manager, all during changing eras in settings reflecting an evolution away from the culture of institutional custody, isolation, and total control post-Willlowbrook. I left the human services field for a few years to use other skills and change my basic work orientation for a while. I returned to human services as a Social Recreational music specialist and as the interim Para Transit Assessor in the Bridgeport region. This led to an opportunity to work for WDOM, with whom I collaborated during my Case Manager work years. I knew WDOM’s previous Executive Director through the political music world; he was a major member of the Disabled In Action Singers, whom I had photographed for an album project, and he wanted both my Para Transit knowledge and service plan experience. I started work here in July 2010 as a Case Manager (Service Coordinator); I collaborated with the Social Worker & Program Director of WDOM, and he became my direct supervisor. The Independent Community Living outlook and approach of WDOM at its core appealed to me very strongly, and I welcomed the change in approach that this sphere of social services offered. I always enjoyed mentoring co-workers and performing staff development and skill training; I was appointed the NHTD Program Supervisor & Quality Assurance Coordinator about 2 ½ years ago.

What inspired you to become involved in this field? Do you have loved ones who are disabled?

Two situations moved me toward this vocation. The first was the exposure of institutional environments in which persons with developmental (especially intellectual) disabilities were imprisoned, in documentaries facilitated by the reporter Geraldo Rivera in 1972. To call it shocking and outrageous is a starting point. The second was the birth of a child with Down’s Syndrome to the family of a softball-playing partner on my street in Yonkers. This girl’s mother defied the then-typical advice by the family physician to ‘put her away’ (institutionalize her). The late 1960s had influenced my valuing of work which could improve social ills, and this was a concrete way to do it, instead of arguing about revolutionary ideology. I had a college friend who became an institutional social worker, and he convinced me to respond to a recruiting effort on campus by Manhattan Developmental Center (actually, a smaller version of Willowbrook, at that time), operated by the NY State Dept. of Mental Hygiene. So, I was hired as a Therapy Aide, a direct care position. I had absolutely no clue what I was in for!

My son has developmental disabilities, along the higher end of the Autism spectrum. That happened well after I had started social services work. It did trigger my becoming a Parent Advocate with the Yonkers Exceptional Child PTA. My life’s work experiences helped me to become a more effective advocate and resource guide for him and other similar children and families. Several of my more knowledgeable colleagues and supervisors provided useful advice, so I’ve had roles as both a provider and a recipient of support.

What do you love most about your role with WDOM? What aspects do you find most fulfilling?

I love providing options that people had no clue existed. It makes a huge difference in their life and their family options. As a Service Coordinator, I’ve gotten to help undo or prevent the kind of isolation from the community, which existed in the institutional settings, in which I had started my social services work. Nursing Homes are the last major institutional warehouses of persons with what are considered undesirable disabilities. Even psychiatric institutionalization has declined as the general way of addressing the needs of persons with severe psychological disabilities, more so than Nursing Homes have. We get to work directly against such dehumanization and prevent it as well. I also have fascinating coworkers. We have people here who have disabilities; most of us have some, visible or non-visible.

The best times are when a client states that we’ve provided help without which they couldn’t have successfully re-entered or stayed in the community. I’ve seen how providing information about options, resources, and rights, which our clients or their families hadn’t known about makes a change you can feel in their morale; it hits like a wave.

What would you say are the most significant highlights and your proudest achievements during your time with WDOM?

As a staff mentor, I’m grateful to have the chance to facilitate the technical skill development of new service coordinators and illuminate the outlook of service approach from the independent livingperspective,with good practical sense. Their significant growth in these areas and the increasingly effective self-direction in their work are exactly what a mentor hopes for. I received guidance from many mentors in my career, and I am grateful to be in a position to ‘pay it forward’. For someone with long experience in a vocation, it’s essential to pass the torch to those coming next, to advance our mission into the next era and future generations. Progress doesn’t occur by coasting on past momentum.

Some case highlights include:

• getting people out of nursing homes who had been told that they’d never be able to do anything anymore on their own, by Nursing Home operators or sometimes their own families (thankfully, not very often);

• helping people obtain affordable housing, and linking them to supports (some of which had been unknown to them) to maintain that affordability;

• As a health care Navigator for about 2 years with WDOM, the insurance, that I helped one family receive despite technical obstacles enabled their daughter to have a life-saving cardiac operation.

• Successful liaison between some of my clients and their landlords to resolve difficult relationships and broker agreements to keep them from eviction;

• Working with a home care Aide, getting extremely ill (with COVID, it turned out), hospital-phobic person to accept treatment at a hospital that she trusted, and convincing EMS to extend its transport region to take her there.

What are some challenges you have faced in your current role? What are the biggest hurdles you see facing the NHTD Program?

In Case Management/Service Coordination: finding a balance between what services I expect to provide and what my clients or their representatives (e.g., family advocates and POA holders) can do themselves. That is the most frequent friction point inherent in the Independent Living outlook; the NHTD program (as is the Traumatic Brain Injury program) stems from this philosophy and the social-political movement concurrent with it. Also, how much of a given resource is available at any time fluctuates, e.g., various subsidy amounts (SNAP; Housing Subsidy vouchers or funds); available and affordable and/or accessible living units.

As the NHTD Supervisor: providing critiques that are constructive but not humiliating or embarrassing to the case manager; deciding on which work aspects carry the most weight; transitioning from ongoing direct guidance to providing the opportunity for Service Coordinators to stretch their own wings; pushing toward excellence but not perfection (which can’t exist, anyway, among us humans). In terms of helping people to last in this line of work, a significant personality quality is an essential goal: to give full effort in servicing each person, but not tying self-worth to success in every goal, making everything right for someone, or similar emotions. Again, neither we nor our clients are perfect. Not every relationship is going to be a perfect match, either. All of this advice is easy to give but can be hard to follow. Being a good professional model is a best practice goal for me.

Where do you see yourself and WDOM in the next 5 to 10 years?

That’s tough to answer. I think we may need to defend gains that we thought were permanently won: support for an all-inclusive community, belief that there are no useless persons, belief in the right to life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness; and funding to support those who struggle to stay afloat. WDOM may need to be fighting attempts to reverse this progress and fight the return of ‘Survival of the Fittest’ as a philosophy and (even worse) as a practice. Having to do this plus simultaneously advocate for better levels of funding for our efforts to support independent living services provided by agencies like WDOM is an unfair burden and an almost impossible task. But if we and the movement toward a humane society are stopped or reversed politically and socially, neither WDOM nor any other social service/advocacy organizations might survive in 5 years. Politics shouldn’t have to be a significant focus of the social services world, but we may not be allowed a choice in the matter.

As for myself, I had no anticipation of a) this becoming my vocation; over time in my first 2 or 3 years in this career, I discovered that I had the capability of gaining skills in it, and I developed them beyond what I had imagined; b) I didn’t plan to stay in this work as long as I have, but it did happen. I’m almost 71, so I’ve stopped making predictions for myself. I’ll keep going as long as my health and skill level allow me to. The mentoring and advisory role, which I’m currently in fits me at this stage; I feel that it’s where I should be now.

I bet you have many fascinating stories about the individuals you’ve helped. Would you like to share some?

A fellow came to the day program I was working at, and in his leisure, he played solitaire. I never had an easy time learning solitaire, and he finally taught me how to play without cheating. Another one of my clients had a gift for origami, and she would make these origami birds that looked like boats, that would actually float. She tried to teach me, and I was too slow a learner for it. Also, some clients were more interested in politics than my own sister was, so I taught them how to work the voting machines; it was nice to see civic involvement in that population. There were other individuals who had wisdom beyond what you would think.

Some of my clients are still working and have technical skills beyond what I can do. I have a few people with spinal cord injuries on my caseload, and one of them is an entrepreneur who has a computer consultant business. A lot of these folks have taught me things and have had interesting life experiences. If you had to ask if there’s a typical profile of any people of the various world of disabilities that I’ve worked with, I would have to tell you that if you’ve met one person with a disability, you’ve met one person with a disability. I’ve had a couple of people with paralegal experience too, and they were almost as well versed as their lawyer in terms of appeals for benefits. You get a whole range of experiences just like any community. By keeping them out of nursing homes we keep them as community members. It makes a big difference between how people express themselves, and how comfortable they are with being themselves, which is very different when people are in the community as opposed to when they’re in an institution.

Work aside, what are your hobbies, and what do you like to do for fun

Music playing and concert production; repairing musical instruments and building them; maintaining computers and keeping them from planned obsolescence; repairing things around the home, sometimes re-purposing items to do it; reading sword & sorcery novels and some sci-fi, and reviewing them online; reading history; continuing interest and research in classical and near eastern history and religion (my undergraduate minor) and comparative religion history; bicycling and rowing a boat with my wife; traveling to some favorite places where you can connect with local people: Mohegan Island, various places in New England, San Francisco, Ireland (where my wife says that I left a piece of my heart); maintaining long-distance contact with friends; photography (portraits and photo-journalism; abstract; special effects); wrote for music magazines; discovering music on the internet; serious baseball fan; plants.

Thank you, Gerry, for your thoughtful answers and for taking the time to share a part of yourself with us. So much appreciated.